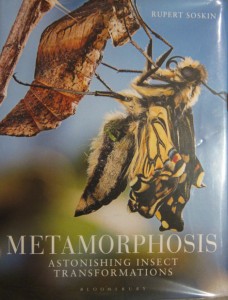

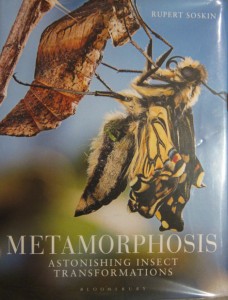

Metamorphosis – Astonishing Insect Transformations – the subtitle definitely describes the content of this book by Rupert Soskin.

Insects – often overlooked, thought of as bugs or pests, possibly with the exception of butterflies (although the cabbage white butterfly springs to mind) but with around one million species known and named. Untold numbers are still to be found. Contrast that with birds – ten thousand; mammals – five thousand; even reptiles and amphibians only manage fifteen thousand between them. It is no surprise then that there are many things that even the most fervent entomologist can still learn about this diverse class of creatures.

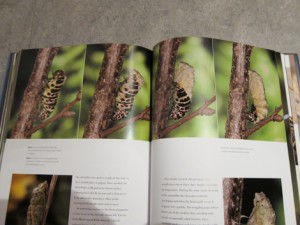

In Metamorphosis the author beautifully illustrates an area that I haven’t yet seen covered in another book – the transformation that insects must undergo to get from an egg (in the majority of cases) to the adults of the species that we are usually most familiar with. This lack of familiarity is despite the fact that the adult stage is usually the shortest with many living days or weeks but spending years as a larva or nymph.

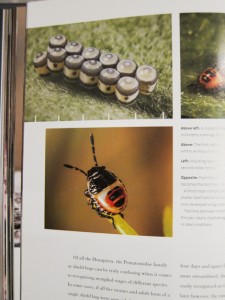

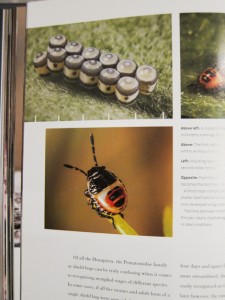

The book is essentially in two parts – those insects that go through several instars (stages); looking to some degree like miniature versions of the adults, and those that undergo a complete transformation from what is essentially a tube of innards to something completely different (the most obvious example being the change from a caterpillar to a butterfly).

I started off wondering so much of the book was devoted to the first class of insects; the hemimetabolous insects (the young of which are called nymphs) when the changes they go through are nowhere near as marked as those of the holometabolous examples. But, as the author explains, the only way that an insect can grow is to shed its skin – and, in some cases (such as some of the shield bugs) I don’t think many people would match juvenile with adult.

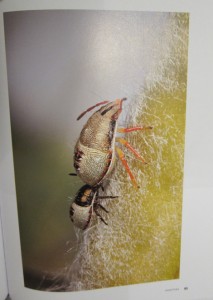

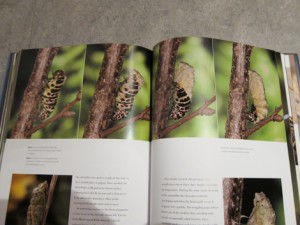

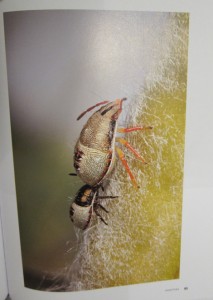

What makes this book a joy to read are of course the photographs. Where many books show the adults in all their glory, Rupert Soskin shows the different stages in the life of the insect, from egg to larva / nymph, to chrysalis and adult.

The photographs are beautiful and I can only begin to wonder at the patience of the author as he waited to get the shots. Within the different chapters there are of course notes about the insects and their lives – after all, the photos only tell half of the story. In some cases he has even shown the scale of the insects – a very helpful device.

I was a little disappointed at first when I saw how many of the insects are from outside the UK and therefore something I am never likely to see (no matter how much the climate changes). But, they were fascinating – I was completely won over by the stick insects and the Peruvian Horsehead Grasshoppers.

All the main orders are included from grasshoppers to mantids, dragonflies to beetles, butterflies, moths, flies bees, wasps to hemiptera. I began to wonder how he decided what to include and also what didn’t make the final cut.

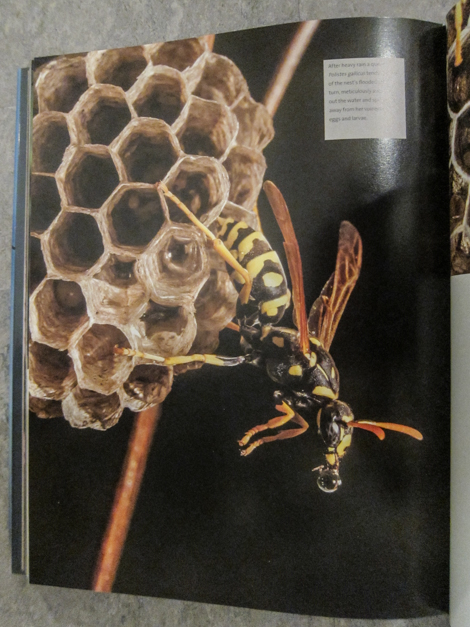

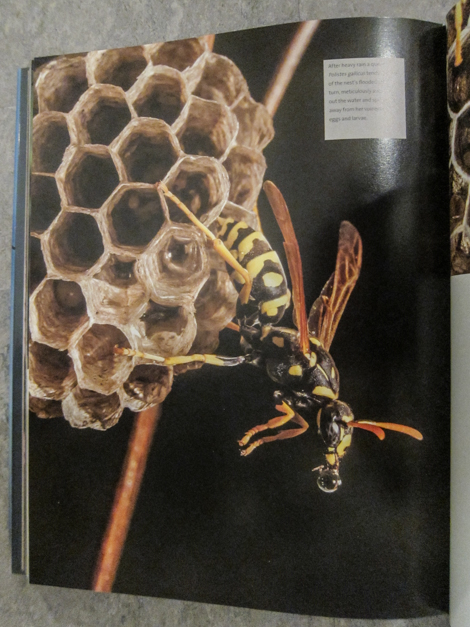

I thought that the sections on the butterflies and moths were interesting choices, showing the changes in size and coloration of the caterpillars and the resulting adult. But, my favourite photo of all (other than the horsehead grasshoppers, mantids and stick insects) had to be the female wasp removing water from her nest after the rain – just fantastic, one of the best insect shots I have seen and behaviour I hadn’t heard about. Just one of the many interesting aspects of insect life that Mr Soskin managed to capture and share.

I have only two real complaints about the book; I would love to have known more about how he took the photos – he has a small section about this but it was very short on actual details and I would have liked it to have been twice the size with more fantastic insects and beautiful photos (this is of course selfish as the book is 250 pages long).

This is a beautiful coffee table book that I could look at again and again, and a starter for anyone interested in insects showcasing some of the less well known stages of their lives. Whilst it is only a starter, it does include some further reading suggestions that will be making an appearance on my birthday wish list. Many thanks Mr Soskin for creating such a wonderful book (and to Northampton Library for stocking it so I didn’t have to wait until my birthday to read it).